A Spring of Bittersweet Melodies

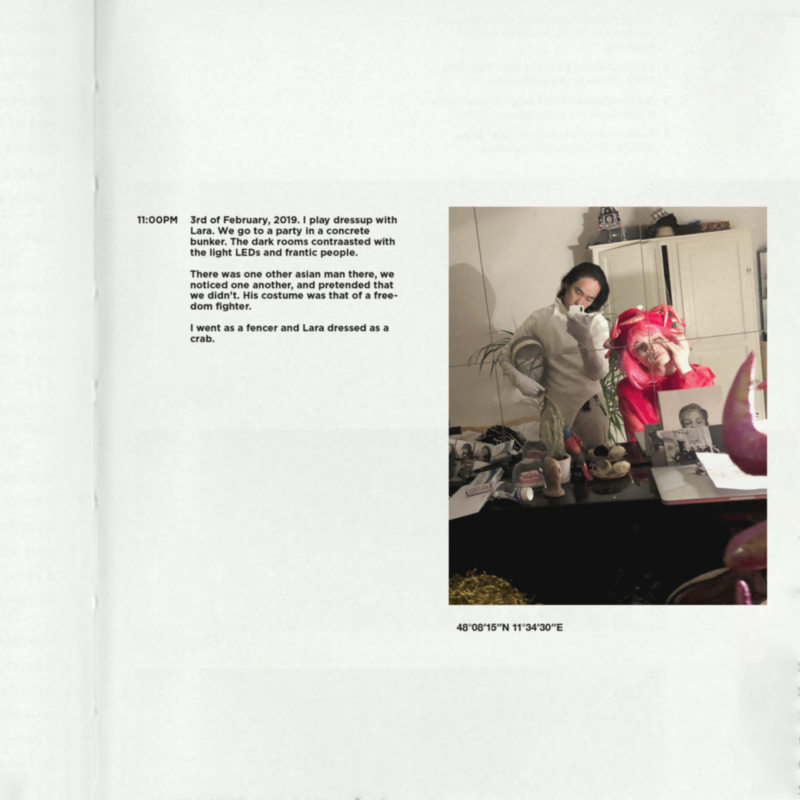

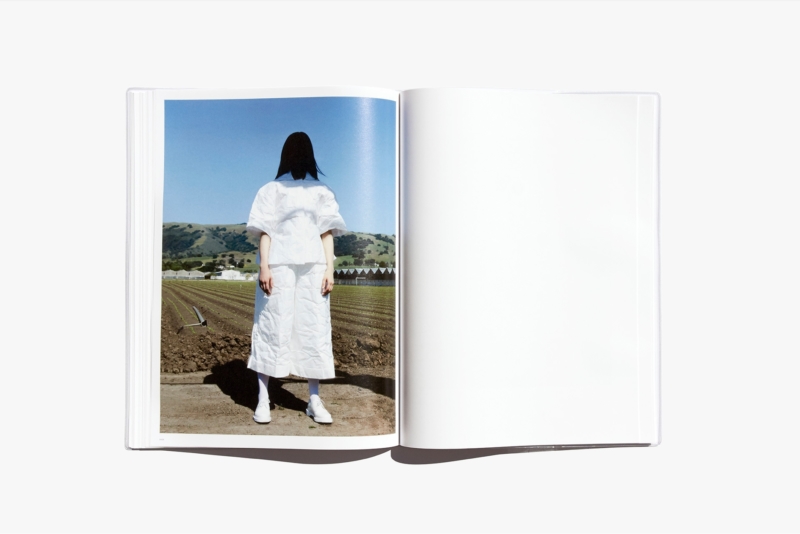

Photography and words by 鄭博榕 aka Ayoto Ataraxia, published in Far Near, Vol. 5, Divergence.

Special thanks to Lulu Yao Gioiello, Justine Liv and Ariana King for the edits and encouragement.

Foreward

Between the inception of this assignment and its publishing, my understanding of the world has changed drastically, particularly since October 7. What feels like cruel irony, my observation and critical voice of Coco Capitán’s work for LVMH, particularly the image of Boy in Green (a photograph of an anonymous Mongolian boy) and the subsequent interview with Gem Fletcher on her podcast, The Messy Truth, has revealed the authoritarian refusal for freedom of speech and critique. Albeit the subject matter is not of grave consequence, it revealed to me the chilling reason which, if unquestioned, leads to the alienated and apathetic society that stands in violent silence during a genocide.

This volume of Far Near questions what we idolize and gives an ode to divergent voices—artists who follow their gut even in the face of ridicule and who express passionate outcries of love despite opposition. In this portrait series of Enji and Urna, the gaze of their journey within the structure of colonialism and orientalism, but also where do I, the photographer, the journalist, and fellow nomad situate in this story?

Prelude

In February 2023, Lulu asked if I would like to do a portrait series of two Mongolian singers in Europe. It had been four years since I took on a photographic assignment. I felt like a washed-up artist, unemployed since the pandemic. Statistically, the government would label me as “retired.” Spiritually, I’m “disconnected.”

Lulu sent me the brief: Enji Erkhem was based in Munich and would be traveling to Berlin for a recording, but I would need to travel to Bagnoregio to find Urna Chahar-Tugchi.

But let us rewind momentarily to the beginning of the pandemic, during the summer of 2020, when a Spanish fashion photographer named Coco Capitán was hired by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy to embark on a Mongolian journey for a glorified advertorial. The resulting project consisted of solemn portraits of unnamed and unidentified Mongolians, and the following year, a podcast episode on Gem Fletcher’s The Messy Truth, in which the photographer spoke at length about the discomfort and disappointment she experienced during her less-than-idyllic journey, a fantasy ruined by a lack of wifi, COVID-19 and unfriendly train passengers. At best, it appeared to be innocent multiculturalism and, at worst, inflight reading material.

Was this not Edward Said’s main critique of Orientalism par excellence? Apropos to contemporary understanding of the historical construction of Western representations and stereotypes of the East? Was the project not the latest iteration of neoliberalism utilizing cultural whitewashing to fund corporate greed?

Who has the privilege to benefit, mine, and reap the identities and bodies of non-whiteness? These are the ones who simultaneously maintain undisturbed supremacy and increase corporate profits under the veil of answering the public’s demand for “inclusion and diversity.” Who appointed these new priests of modernity, who gate-keep exoticism and ever-renewing beauty standards?

I took to Instagram to speak on the topic. I hoped for further awareness and discussion of Orientalism, an issue that my closest European friends around me were ignorant of. The most common response was, I’m so surprised to hear this. It was as if the symptoms of violence were just another iteration of negativity for which people didn’t have the space or time.

In these times of exhaustion, as observed by philosopher Byung-Chul Han in his book, The Burnout Society, we cannot deal with the fragments of a world steeped in violence. He writes, “The violence of positivity does not deprive, it saturates; it does not exclude, it exhausts.” We’re swimming within the violence, and still, we’re asking where the water is. The symptoms of violence are there in the crumbling of our cities, in the vacant stare of the unemployed, in the quiet resignation of those trapped in a cycle of poverty, while having to be reminded constantly to “work on ourselves.” It’s in the screaming videos on TikTok but also in the silent stories of what is not posted.

2020 was the year in which US media regularly accused China of using its social credit system to control and punish its citizens. I remember my first trip to China. I was curious about what it was like to be living on the other side of the information wall under an authoritarian regime. I was curious to speak to people who were fed and believed in a different set of ideologies. Feeling superior, I wanted to enlighten them about the light outside their Platonist cave. What I discovered instead was the disturbing realization that I, too, was chained to a set of ideologies.

Here I was on Western social media after writing about views on Orientalism. My comments were quickly removed, I was blocked by those I had invited into public discourse, and finally, my account was suspended via an anonymous report with the following warning:

“We received a legal request to restrict this content. We reviewed it against our policies and conducted a legal and human rights assessment.”

Shortly after, JP Morgan Chase also wrote me a letter declaring that they would be foreclosing my bank account without explanation, freezing my assets and banning me for life.

The persecution and dehumanization of bodies like mine and the Mongolians Coco Capitán captured and fed to LVMH, veiled under the guise of camaraderie and beauty, remind me of the hypocrisy of neocolonialism. To quote Okakura Kakuzō, “We are pictured as living on the perfume of the lotus, if not mice and cockroaches.”

But the irony was not lost on me. I excitedly agreed to embark on this diametrically opposing project to interview Enji Erkhem and Urna Chahar-Tugchi.

—

Enji Erkhem

We met for the first time at the hotel bar in Berlin. She had just finished her recording with musician Simon Popp. She spoke of the art of improvisation. “We collect moments,” she said. “From morning to evening. Sometimes, I have words, a poem, or a melody. Sometimes, he has a groove, a vibe. We then improve the idea from there. It improves my other—the other part of me.”

Having been raised with Eurocentric classical piano and violin training by Russians, I personally find it stressful to be free and improvise. Alejandro Jodorowsky once said, Birds born in a cage think flying is an illness.

She showed me the album on her Bandcamp: 031921 5.24 5.53 – named after its recording date. I pressed play on “A,” a 9-minute track, and was whisked away from the bar, hotel, and Berlin. Bells, chimes, and acoustic percussion like river stones flowed through my mind. Enji’s voice soared above it all, evoking thoughts and memories. The new album will be another improvisation. Their performance will have no cuts or edits. “It has to be imperfect in their moments,” she said — a deliberate imperfection.

In 1956, Canadian pianist Glenn Gould released his seminal interpretation of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. He was the first classical musician to extensively use tape editing to achieve the precise sound he desired, Frankenstein-ing his creation with each note from different recordings; all this was way before digital music editing. Some criticized his editing techniques as sterile and artificial, while others praised his approach as innovative and groundbreaking. Seven decades later, Enji and Popp were in Berlin recording their improvisations without edits.

We went to her hotel room for a portrait sitting. She showed me the clothes she had brought for the photoshoot.

“Red is my color,” she said, showing me a red jacket and a light blue blouse. “I love patterns—patterns that remind me of clouds or flowers. It’s made by my sister, and with her husband, they have a small business together in Mongolia.”

Enji was born into a family of singers, yet she was the first to tread the path of music as a career. Initially, she ventured into music teaching, but fate had other plans. A jazz project in Ulaanbaatar caught her ear, leading her to audition as a pianist. She was accepted as a singer via an audition led by Martin Zenker, the founder of the Goethe Musik Labor Ulaanbaatar.

She explained the difference between Mongolian and European music traditions, “I sing a traditional form called longsong, which comes from Mongolian folk. It comes from the simple lifestyle of Mongolia. Mongolian music is pentatonic, very different to Western sounds. But it’s an idea of music or dance which reflects daily life. It reflects nature and the experiences of the people there.”

I had never thought much about the Goethe Institute, which receives funding through Germany’s cultural budget as part of its soft power strategy, as countries diversify their military spending into cultural influence. The Goethe Institute has faced criticism for ignoring marginalized groups and promoting colonialist attitudes. But it is also through these cultural institutions that Enji can preserve her folk heritage.

“You’re also interviewing Urna for this project, right?” she asked, her eyes widening. “I discovered her when I started to do serious music. I’ve been listening to a lot of her music. When I performed here in Germany, someone would ask me about her and tell me that I reminded them of her. But we sing with different dialects. I appreciate what she’s done. She’s a beautiful artist.”

“What is the dialect that you sing?” I asked.

“I don’t know if I can talk about that because they are sensitive about the theme.”

“Oh,” I said, surprised. “Who’s they?”

“Inner Mongolians. There’s a lost connection between the Inner Mongolians and the Mongolian Republic. Inner Mongolia is an autonomous region of China, and the two cultures have been separated for many years. Sometimes Mongolians don’t like Inner Mongolians.”

Enji spoke of the Mongolian diaspora, like the Khalkha, the Buryats and the Oirats. The Mongolian Republic has undergone numerous revolutions and changed its script to Cyrillic in 1941. She can read Russian but not understand it, while previous generations can speak fluent Russian due to their close ties with the Soviet Union. As a jazz singer, Enji still sings in Mongolian.

“…if I have to express my words and feelings, I must do it in my mother tongue,” she said. “I find the language very rhythmic. I try to keep it sacred. I don’t use everyday speech but in proper Mongolian language. It’s a poetic language. The Mongolian language has expressions and words that we’ve forgotten.”

I returned to the portrait at hand. I realized that this had been my first photographic project since 2019. Roland Barthes’ 1980 book Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography argues that photography can objectify and fixate individuals, transforming them into mere subjects of the photographer’s gaze. The photograph, he posits, captures only a fleeting moment in time, retaining a specific pose or expression that may not fully encapsulate the subject’s true self. In this way, the individual becomes a mere representation – a shadow of their former self.

I thought back to Coco Capitán’s The Boy in Green and his averted gaze, another reminder of the neocolonialist relationship between photographer and subject. What was the relationship here, then, between Enji and me? She told me about the new track from her new album, a melancholic dream of severance from her mother. On first reading, the dream speaks of individuation and the sublimation of melancholy into gratitude. But is this not indicative of a larger pattern? A reminder of migration, severing from Mother. Mothertongue. Motherland.

The spring rain had passed, and we walked to Geschichtspark Ehemaliges Zellengefängnis Moabit, a memorial site preserving the history of the former Moabit prison. During the Nazi regime, it held political prisoners. The site now promotes dialogue and awareness about past and present issues. The prison closed in 1955 and was one of the largest in Germany. Here, in the present, I took portraits of Enji.

We spoke of our lives in Germany and the changes through the pandemic—the difficulty of learning German and the violence of assimilation. I asked if she had any food preferences.

“Unfortunately, I eat meat…” she said apologetically.

“Do you feel guilty about eating meat?”

“Not really. I can have it. But if you’re with people, you have to follow….”

“But why do you say, unfortunately?”

“I feel that I am being offensive.”

“Is it from being in Germany?”

“Yeah…bio and everything! A drummer I know is very kind, but he’s very focused on that stuff. Everything vegan. Bio! Even with clothes! But I cannot afford it!”

How does one mitigate the contradictory forces of new forms of ideology while maintaining cultural and economic choices in the ever-flattening forces of the hegemony? The Mongolian soft power of influence I remembered as a child was the meat-centric restaurants of Mongolian barbeque.

“It’s all about meat!” She said. “Nothing else! I also grew up in a typical Mongolian family. We ate from morning to evening meat! Just meat! Breakfast meat. Lunch meat. Also, very warm dishes. I need warm dishes!”

I took her to a Bavarian restaurant where the servers wear dirndl and lederhosen. Enji’s Mongolian outfit enamored the waitresses at the restaurant. She spoke of the transition and contrast from the world she remembered in Mongolia to her life in Munich, from sleeping together in a separation-less yurt with the whole family to her first experience in an Airbnb and of the unpleasantness of having one’s own room. But today, her family no longer resides in a yurt.

“It’s such a contrast between the city and the countryside,” she said. “All the young people want to study and work, but the possibilities are in the city. The city is full while the countryside is empty.”

It’s tempting to romanticize folklore and the countryside—an imaginary Eden to return to retroactively. As we ordered food, I asked her about her experiences with racism.

“It was just a one-time bad experience,” she shrugged it off. “It was very harsh. It was at a hotel jazz club. I played a small gig with the piano in the room. And…I already forgot it,” she said, repressing the subject.

I considered my relationship with the taboo topic of racism. Is it not dissimilar to other hegemonic pressures like ideological veganism? The experience of oppression of Asians in the diaspora has frequently been a minor issue. But who is the big Other that suppresses our speech?

“What did you listen to as a child?” I tried changing the subject.

“Folk songs. Traditional Mongolian songs. But I also listened to what other girls listened to: Christina Aguilera, Beyoncé, and whatever’s on the billboards.”

She spoke of modern pop in Mongolia, how they mix techno with traditional music, and her feeling of disconnect.

“It just wasn’t for me,” she said. “That was clear. I didn’t want to live like that. I like to sing. But I couldn’t imagine myself singing [pop music] on stage. I was lucky to have teachers like Martin Zenker…with jazz, you have to be your voice. You have to be the change yourself. I found comfort in that. It is more focused on music than being famous.”

As we shared a warm meal, she spoke about her experiences living and touring in Europe. She was invited to London by the BBC but was refused a visa. The reason given in the rejection letter claimed that she would not be able to support herself financially in London for a week as she was from a “Third World” nation, despite having invitation letters to perform at Koko Theatre in London and alongside music legends such as Pharoah Sanders, as well as an invitation from broadcaster Gilles Peterson to perform at Cafe OTO. Other Mongolians received the same refusal. I thought about the effects of blatant racism compared to systemic systems of oppression and her resilience despite it all.

“I was sad and upset. But it’s ok,” she said, then perked up. “I have applied for a musician visa. If it doesn’t work, it’s not the end of the world. But it was the first time I experienced rejection because of my background.”

We left the restaurant in search of coffee. I took her to a Japanese cafe that served matcha and mochi. She said she’d never had them before. So I got her one of each. She smiled with curiosity. We shared afternoon tea and snacks at a streetside cafe and discussed the nature of inspiration. I felt her resilience. She could be in Munich or any other place, but that didn’t change who she was. I enjoyed our talk under the cumulus clouds on music and process, forgetting the world’s noises for a moment.

We listened to the rest of her album in the car as I drove her back to the hotel. A thunderstorm rumbled in the distance. I felt, once again, in a different world—outside of Berlin, inside the car, together.

—

Urna Chahar-Tugchi

I was informed of a nationwide labor strike in Germany through a promotional text from my car-sharing app the night before my trip to Italy in search of Urna. That didn’t help my neurotic anxiety. I decided not to risk taking public transport and went with the car share with plenty of spare time but ended up circling twice at the airport because I missed a turn, and my bladder was about to burst from the copious tea I drank in the morning. As I searched for parking, I received a text from Urna.

—Are you in Berlin, or are you on the way?

Shit. I hope she’s not canceling at the last minute, too.

—I’m in Berlin, about to board the plane. Is everything ok?

—Yes, everything is fine.

She then texted me a photo of vinegar I recognized. 镇江香醋 (Zhenjiang Balsamic Vinegar)

—if you pass an Asian shop, please buy 3x vinegar. Chinese 3x souja sauce. Good trip.

Coco Capitán took the Trans-Siberian Express to Mongolia. I took a Ryanair flight FR134 to Rome from Berlin to find a Mongolian. After landing, I got a rental car. The clerk at the rental desk gave me a free upgrade, a Citroën C1.

“Where are you going?” She asked.

“Around Orvieto,” I said.

“For business? No one goes there other than business. It’s quite boring,” she told me, as a matter of fact.

“I will pass by Civita near Bagnoregio,” I said. Was I searching for validation from the rental car receptionist for my voyage now?

“Oh, that’s beautiful! One day, that city will disappear,” she said with a smile. “Please remember that I gave you an upgrade. Don’t forget to give me five stars after you receive my email.”

The sweet nothings of flirtation at the service desk have long departed. As I navigated the streets of Rome, searching for Zhenjiang Balsamic Vinegar and soy sauce, the city’s ancient allure was but a distant memory.

Instead, I found myself stranded at an Alimentari Oriente on the city’s outskirts, reminiscent of a pool shop. Two befuddled Filipinos gazed at me quizzically, unable to provide my desired condiments. Alas, I had to seek another alternative, dreading the Roman congestion. The alluring charm of the city had been replaced by a fixation on traffic: a symptom, perhaps, of being a local as opposed to a voyager.

I saw trees: the umbrella pine and the penciled cypress. Nuns appeared. It started pouring. Rain turned to hail as I circled by the Colosseum for parking. A small Suzuki passed me by. Inside, a man smoked a fat cigar. He wound down his window at every other intersection to vent before closing them again, returning to his cigar steam room. The hailstones grew in size. Where was this damn Grocery Shop of the Orient? I thought, glaring at Google Maps.

At the third shop attempt, I asked the Asian grocer in Italian if they carried Aceto di Zhenjiang. He looked at me with a confused face. His colleague told him in Mandarin what I was looking for. Relieved that he also spoke Mandarin, I switched as well. The man responded in Italian. The two then continued to speak about me in Mandarin as if I didn’t understand. I gave up. I bought six bottles of off-brand soy sauce and white vinegar, got back in my car and headed north.

After a hundred kilometers, vineyards appeared. The spring wind picked up speed, leaves blew off. Roads narrowed. All I could think about was what people would order on Amazon here. Chinese rice vinegar and soy sauce, perhaps.

The map indicated the last turn; the asphalt was now dirt. Two leashless white dogs ran out. Urna didn’t send me her address, just GPS coordinates. The path led me to a tree. Her car, parked next to it. Her house nestled in the field: an a-frame single-story building. The grass, freshly cut. Laundry out front. A feeding bowl for the wild cat.

I knocked on a glass door. Urna appeared out another. She welcomed me with a warm hug. I noticed from the get-go her exuberance. She offered me Mongolian tea—a brew of black tea, salt and fresh milk. I don’t remember the last time I’d had fresh cow’s milk. But hey, when in Rome.

She laid out biscotti, crackers, cheese, sugar, butter, and a jug of water on the dining table and a wooden and silver dessert spoon for each, then raced back to the kitchen to brew the Mongolian tea. The table was next to a fireplace and two other Mongolian-styled seating arrangements. On the floor, a Mongolian-styled chaise lounge faced her large set of speakers, framing her extensive collection of CDs. She inserted a disc; Terem Quartet played Variations on Swan Lake with sounds of domra, balalaika and accordion. The music then flowed to Ashkhabad’s Bayatilar—a song by Azerbaijani composer Eldar Mansurov. The familiar track contained sounds of dutar and the gopuz. It made me want to stay where I’d never been. I skimmed through the living room as Urna moved with energy throughout the house. Her library was filled with Mongolian books and CDs: Sasha Pushkin. Boom Beat. Maria Callas, 52 CD set. Photos of her family and artworks from her friends and godchildren.

We finally sat down. She placed three slices of Parmigiano into my cup before pouring me a large Mongolian tea.

“In Mongolia, the first time you arrive in the house, we do not give empty,” she said. “So you will try, if you don’t like it, just tell me! I have a lot of other teas! This is something special because it’s with milk and salt.”

“I’ve never done this before,” I said as she offered ghee for the tea. “I’ve never had salted milk tea with ghee and Parmigiano.”

“Ah,” she laughed. “This is totally Mongolian.”

Urna was born in 1969 in Inner Mongolia, an autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China. She speaks, in addition to Mongolian, Mandarin, German and English. She also picked up Arabic and Shanghainese along the way. She is now learning Italian after having moved here a year ago.

“What city in Mongolia were you born in?” I asked, sipping the tea.

“Grasslands! There are no cities! It’s only the house of my parents. A lot of animals. Cows. Sheep. Horses.”

At eighteen, she ventured to Shanghai to study despite strong resistance from her family. Shanghai, as she described, was another planet for her, coming from the Grasslands. But she had met a teacher who taught her dulcimer—Chinese dulcimer—in Hohhot, the northern part of the People’s Republic of China. She had agreed with her family that she would be given the opportunity to study for one year, after which she would return to the Grasslands. But her teacher’s work was transferred back to Shanghai. She was devastated by the news but soon after received a telegram from her teacher, who had prepared her to travel and study in the metropolis. But her family was not so enthused.

“Shanghai is another world for us in the Grasslands!” she laughed. “I told them, Anyway, I’m still in the one year of study, Hohhot or Shanghai! But to go to Shanghai, first, it’s two hours by horse, then three days by bus to arrive at Hohhot. And from Hohhot to Shanghai at that time takes two days and two nights. Everybody was against the idea. My best friend didn’t say no, but she didn’t say yes. She just said, ‘If you want…but this is dangerous! Shanghai, you don’t know anybody. You’ve never been there. You don’t speak the language. And you’re a girl!’ All my friends and relatives said the same thing. Normally I don’t know my relatives in the cities. Everybody told me, ‘Even as 30 or 40-year-old men, we’re always two people together when working in the city. Never alone like this! You’re an eighteen-year-old girl! This is impossible!’ My grandfather told me, ‘My girl, if you want to stay in the city, I will give you my permit! You can stay in Hohhot; you can have good work. You can have a good salary! Don’t go to Shanghai!’ I said, ‘No, grandfather! I want to study!’ Then I go! I so much wanted to go to study. I forgot everything! Suddenly, I arrived in Shanghai, only to realize I didn’t understand anything!”

Urna arrived in Shanghai at the end of the ‘80s, not speaking Mandarin nor Shanghainese. This was the Deng Xiaoping era, the era of economic reform. 1989 was also a turbulent year of protests throughout China, led by students and teachers. But Urna was focused on her studies of Mandarin and her music to ensure her place in the university. She spoke in great detail about her arrival and shock as she carried her now redundant Mongolian books.

“In my whole life, this was the biggest shock! People. Cars. Skyrises. That’s all you see! And my ears were not used to the noise!”

The instructions on the telegram given by her teacher were lost in translation. She sat waiting alone at the wrong exit for two hours. As her teacher searched for her at a different entrance of the Shanghai Station, Urna considered her options. It would take another three days if she decided to turn back. But she found the courage to venture into the city in search of her teacher despite not speaking a word of Mandarin. Cut by language, she cried as disinterested workers hurried by around her. Finally, an old man took pity on her and helped her track down the famous university with her teacher’s telegram.

She learned Mandarin in the following six months and found her place at the Shanghai Conservatory. Later, she discovered the Goethe Institute and eventually moved to Berlin. She toured throughout the world, but her Chinese passport proved to be difficult for her travels. She eventually applied for a German citizenship.

“I first arrived in Berlin in ’95. It was a culturally open city,” she said. When asked about her music, she described it as “music without borders.” Interestingly, music is still categorized with an American consumer-centric view: classical, jazz, rock, pop, folk, electronic, and “world music.” Everything that doesn’t fit neatly into these genres gets lumped into the “World”—a refusal of categorization. Urna also resists categorization.

Cultural theorist and sociologist Stuart Hall spoke of “articulation” to grasp the racial politics behind the labeling of “World Music.” He believed identities were not fixed or essential but constructed by articulating diverse cultural elements. In “World Music,” such elements are articulated, not neutrally or objectively, but shaped by society’s dominant cultural and political forces. So where is World Music placed? Is this not shaped by the dominant Western culture, historically associated with cultural and economic dominance? The process of selection and marketing is not neutral. Still, it is shaped by the racial politics of the dominant culture, which involves exoticizing and commodifying non-Western cultures for the consumption of Western audiences. Her refusal of categorization is also present in her collaborations throughout her albums.

“This is part of my culture,” she explained. “Mongolian life is nomadic life. I’m a Nomad. In our culture, we connect different people as a cultural exchange. I love meeting and bringing cultures together. And music has no border. If you meet, you make music with soul.”

Urna collaborated on her last album with Kroke, a Polish instrumental ensemble. Throughout the years, she has made albums with Robert Zollitsch (zither), Oliver Käberer (mandolin), Wu Wei (Sheng), Sebastian Hilken (cello and the frame drum), Ramesh Shotham (Indian percussion), Djamchid and Keyvan Chemirani (Zarb percussions), Zoltan Lantos (violin). Her compositions are part of a tradition from Ortos, also known as the Sea of Songs, also known as 乌拉特. There are dense forests of larch trees that characterize the area. It’s where many traditional Mongolian songs have been composed and performed for centuries. It’s derived from the Mongolian word for soul, a site where the ancestors reside.

“There’s a spring of melodies inside me,” she said. “I want to bring this out. I also do this in concerts. The enjoyment is stronger because this is a direct connection. I tell my audience that this song was only for them because after I finished, maybe I couldn’t sing it again. We have a saying in Mongolian Shamanism: The lyrics are heaven’s language. Or maybe it’s my language. Nobody understands; at the same time, everybody understands.”

She spoke ontologically of her music and the separation from her dulcimer studies. She used words like the moment, existence and nature. The dulcimer was still with her, though kept shut in its case for decades, between her speakers.

We went for a drive around Bagnoregio and visited her favorite spots. She was familiar with the locals, greeting everyone with an enthusiastic Buongiorno. We picked up prosciutto crudo, eggs, pizza crackers and mandarins. We passed by a local church. A man paced, and another woman sat in the pews. Urna took a breath and sang. It was 6 PM. The church bells accompanied her voice. Indeed, she sang in a language I didn’t understand, yet I understood. A reverberating echo followed. We sat in silence.

“You told me you’ve been away from your family,” she said with a knowing smile. “This was for you.”

We strolled through the quaint medieval quarters of Orvieto. She spoke of the heaviness that loomed over the people in Germany since the pandemic. She preferred the light-heartedness in Umbria.

I spent the night in her generous guest room. Snakeskin wrapped around the rafters above the bed.

“Are you scared?” she asked as we stood by the door, looking at the enormous snakeskin.

“No,” I replied.

She told me that the previous tenants had left them there. She thought it was interesting and didn’t remove it. I don’t know if it was the snakeskin or the fresh air of the countryside, but I had the deepest slumber since 2004. We toured around Lago di Bolsena the next day. It was the first time I had returned since 2006 when I sailed with an Italian from Montefiascone—a village where they would fill the fountains with wine during their annual wine harvest.

I departed after lunch. We hugged.

“Wait,” she said, “for us Mongolians, guests cannot leave empty-handed.”

She gave me a copy of her CD—Ser.

I drove to the Roman airport via the seaside. It was an industrial coast filled with shipping containers and parking. I found a desolate beach. I watched the waves crashing. Spitting rain came and went. Looking at my watch, I had another hour before my Ryanair flight. I thought about Coco Capitán’s trip to Mongolia and her complaint about the lack of WiFi. I still had three bars of LTE out here. I took out my phone and opened Instagram. I tapped Post New Story. I framed the ocean and tried to avoid the sight of the shipping container. Did I envy her ability to “discover” and “create” the fantasy of the Orient? Or did I envy her inability to live and share that moment immediately? I put my phone away, took a piss on the rocks, and drove back to the car rental.

—

Coda

Back at home in Berlin, I played her album. I was caught by one track in particular, Laturna (Awakening):

I send my sounds into the universe and connect them to the best wishes for all life on earth I wish there to be only positive news and messages of hope for everyone; My desire for all.

Her voice struck at my defenses. There, sitting at my breakfast table, drinking Mongolian tea, I cried.

—

You can see the rest of the portraits from the story in Vol. 5 of Far Near.

Available for Preorder – Expect delivery in February

Order Here

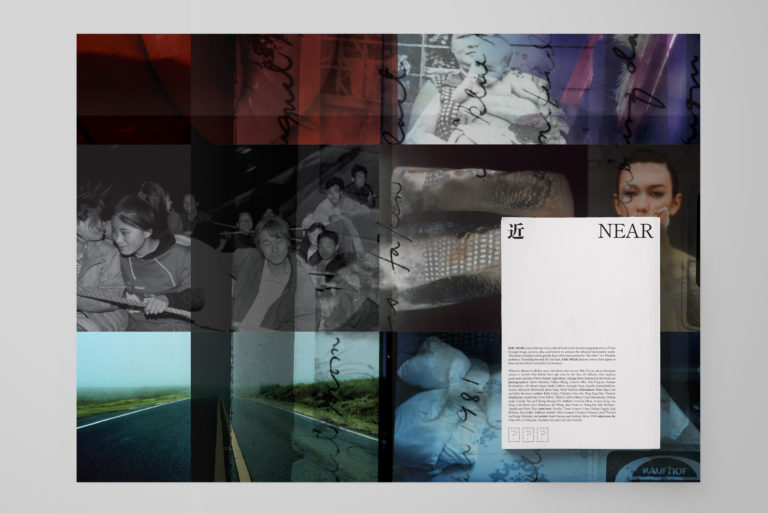

What we choose to idolize says a lot about who we are. Vol. 5 is an ode to divergent voices — artists who follow their gut even in the face of ridicule, who express passionate outcries of love despite opposition. We visit Mongolian singer Urna Chahar-Tugchi living in a remote town in Italy, revisit the beauty and strength of LGBT icon Akihiro Miwa, explore desire and gender in South Asia inspired by Pakistani film Joyland, peer into the traveling circuses of Xi’an through Xiangjie Peng’s photography, listen to Uzbek and Filipino independent music scenes and more.

Among those featured in this book are photographers: Ayoto Ataraxia, Yuhan Cheng, Liberto Fillo, Rob Frogoso, Hassan Kurbanbaev, Ali Monis Naqvi, Keith Oshiro, Xiangjie Peng, Kamila Rustambekova, Saturn, Motoyuki Shitamichi, Irene Tang, Vivek Vadoliya; filmmakers: Phạm Ngọc Lân and Miko Revereza; artists: Bella Carlos, Christina Yuna Ko, Teng Yung Han, Dmitriy Hashhayan, Anchi Lin [Ciwas Tahos], Thai Lu, Alicia Mersy, Urara Muramatsu, Daleen Saah, Camily Tsai and Tseng Kwong Chi; writers: Lucinda Chua, Ariana King, Lin King, Lisa Kwon, Lisa Tanimura, Jiji Wong, Xiao Yumi w/ Wang Da, Mia Winther-Tamaki and Mimi Zhu; musicians: Amalia, Timur Azimov, Urna Chahar-Tugchi, Enji Erkhem, Saru Jadid, Yaikhom Sushiel, Chris Fussner (Tropical Futures), Josef Tumari and Jorge Wieneke; and actors: Rasti Farooq and Akihiro Miwa. With interviews by Clara Peh, CJ Salapare, Sreshtha Sen and Lulu Yao Gioiello.

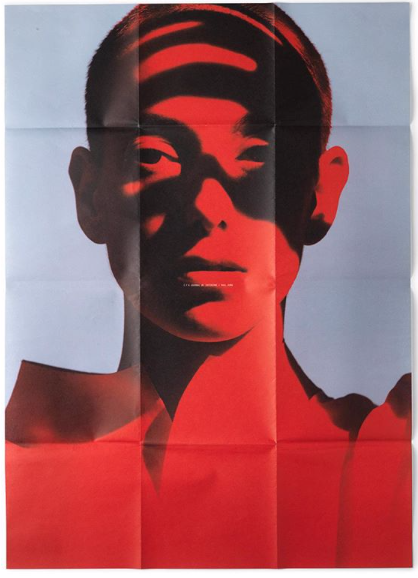

Each book comes with a zine by Urara Muramatsu, two inserts by Christina Yuna Ko and Alicia Mersy and a fold out dust jacket poster.

320 pages.

15 x 21 cm | 6 x 8.24 in.

Swiss bound with glossy, newsprint and uncoated papers.

- A Spring of Bittersweet Melodies

- Beyond Fashion 2019-2023

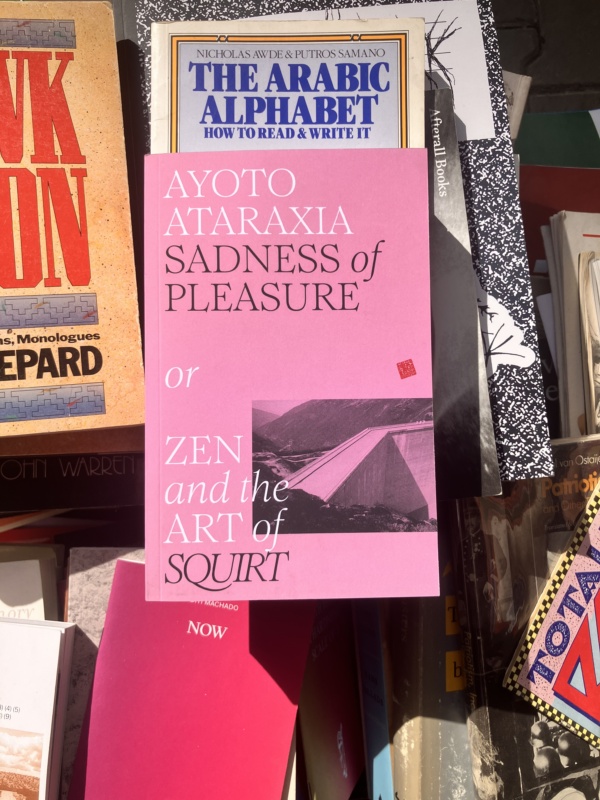

- Sadness of Pleasure: Zen and the Art of Squirt Feb 14, 2023

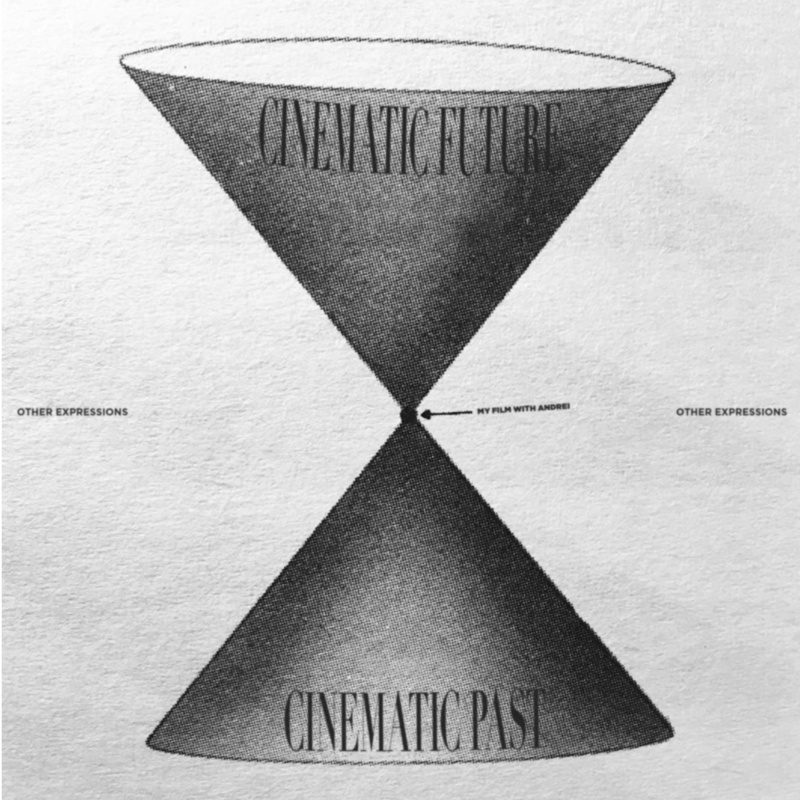

- My Film with Andrei Dialectic 12.02.2022

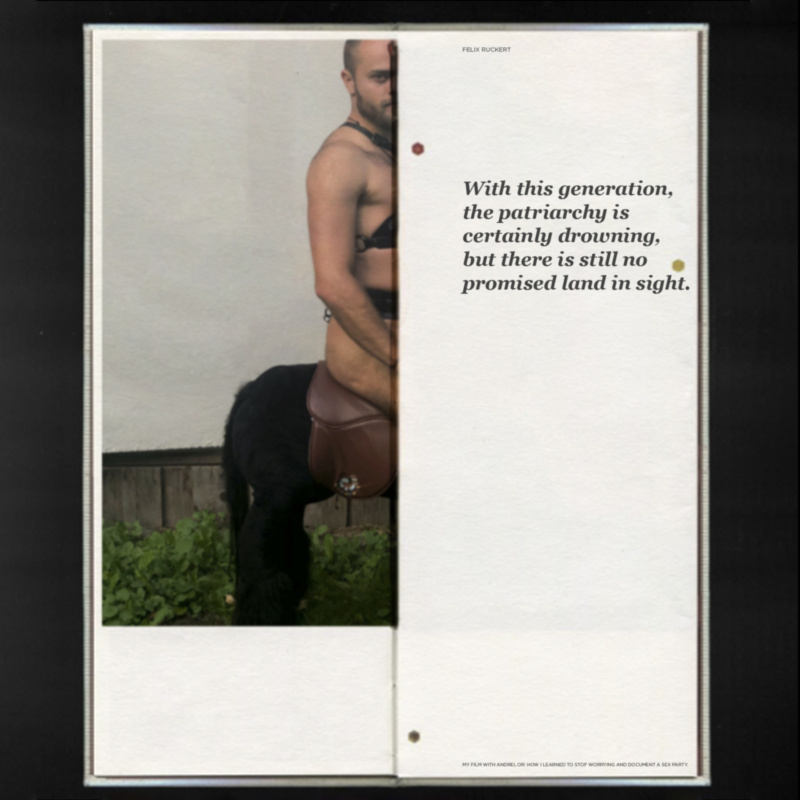

- My Film with Andrei Review by Felix Ruckert 22.01.2022

- Collected writing

- Neoliberal Imagery, Colonialism and Identity

- My Film with Andrei Poster Experiments

- My Film with Andrei, Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Document a Sex Party PRESS PREVIEW (2021) 2021.11.14

- My Film with Andrei | Official Teaser HD (2021) 2021.11.28

- My Film With Andrei Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Document a Sex Party 2021.11.28

- Tokyo Recordings 03.09.2021

- No Country for Diasporic Men album 22.07.2022

- Thomas Azier 2020.10.29

- River Crossing 2020.10.23

- Nowness Asia Interview 2020.07.24

- In Conversation: Thomas Azier and Ayoto Ataraxia 2020.05.19

- Hold On Tight 2020.05.01

- Breathless

- A moment in Paris

- Eclipse of my heart

- P.K. 14 Portraits

- The Moon

- The Room

- PJW577 Bodies

- Future Spaces

- Beyond Fashion Exhibition 2019.01.01

- A$AP Rocky

- Pure Barre

- A new face

- PJW576 Intimacy

- Sunrise

- On the roof with Colleen

- Ana-Leigh

- Feeld — Intimacy Research

- Feeld in London

- PJW572 Vogue Italia 2017.04.17

- The Kinfolk Entrepreneur

- PJW555

- PJW554

- Hermès

- PJW551

- PJW543

- PJW542 Interzone

- PJW541

- PJW535

- Face

- PJW527

- PJW520

- PJW515 2015.10.15

- PJW512

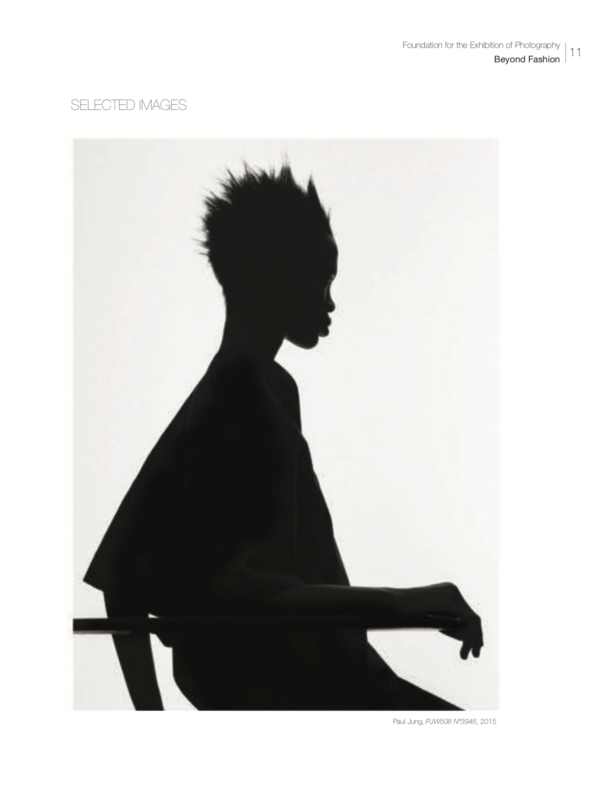

- PJW508

- PJW505 Material Turn

- The Immaterial Turns of Baumeister Jung 2017.10.21

- Violet Hands 2017.12.09

- PJW506 LAB

- Visionaire: Brooklyn Dreamspace 2016.12.01

- PJW504

- PJW406

- PJW391

- PJW388 South Sudan

- PJW381

- PJW373

- PJW370

- PJW369

- PJW323

- PJW320

- Material Turn

- PJW315

- PJW292 2016.05.02

- PJW287 2016.04.29

- PJW283 2016.04.29

- PJW276 2016.04.29

- Metal Magazine Interview 2014.05.08

- Estelle — Conqueror 2014.07.22

- Silicone 2013.12.01

- PJW260 Grovelling

- PJW246 2012.12.01

- Bibliography

- Bio

- CV

Appendix

Credits

NAVIGATION

( F ) for fullscreen

← → for slide navigation

↑ ↓ for entry navigation

Drag to adjust horizontal and vertical dividers for different sizes.